Binh Gia: Before the March1965 landing

Col Eller was serving as the senior advisor to the 4th Battalion, Vietnamese Marine Corps, during the actions described in this article.

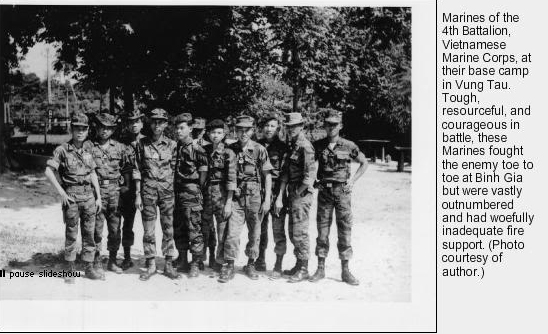

In the waning days of 1964, the largest battle waged during the war in Vietnam up to that time was fought in and around the village of Binh Gia. At the time I was serving as the senior advisor to the 4th Battalion, Vietnamese Marine Corps. The battalion was serving as the III Corps reserve and was encamped at Di An, near III Corps Headquarters and Bien Hoa Airbase. The battalion was committed to the battle and, along with two other battalions, suffered major casualties. This article is written in memory of those who were killed or captured in that battle.

The situation throughout South Vietnam at that time was fragile at best. Following the November 1963 coup that had resulted in the ouster and assassination of President Ngo Dinh Diem, the country was plunged into a year of turmoil and instability. Nearly all province chiefs and district chiefs were replaced after the coup, and a number of top military commanders were relieved. Significantly, the strategic hamlet program, which had been generally successful in separating the population in the rural countryside from access by the Viet Cong (VC), was now in disarray. The VC had taken advantage of the instability and weakness in leadership following the coup to successfully attack many strategic hamlets, thereby expanding its control outside the major population centers. In addition, the VC had launched two successful attacks against Americans—an attack at Bien Hoa Airbase in November, resulting in a number of Americans killed or wounded as well as many aircraft destroyed or damaged, and an attack on an American bachelor officers quarters in Saigon in December, also resulting in a number of Americans killed or wounded.

From the time I joined the battalion in May 1964, the battalion

participated in a number of different operations throughout the III

Corps and IV Corps areas, which generally comprised the southern

half of the country. Although enemy contact was frequent, enemy

forces encountered rarely exceeded platoon size. Periodically during

operations we would receive reports of larger-sized units nearby or

pass through areas recently occupied by much larger units. We

frequently received mortar and sniper fire and regularly suffered

casualties from improvised explosive devices, but the enemy chose

not to engage us in a major firefight, and we were not able to trap

them into doing so. This was to change dramatically at Binh Gia.

During the period immediately preceding the Binh Gia battle, the

battalion had been in near continuous combat of the type described

above for about 3 months. Just prior to Christmas the battalion was

allowed a short break to return to its home base at Vung Tau to

replenish supplies and equipment and to permit the Marines to visit

with their families. On Christmas morning we returned to Di An and

resumed our assignment as III Corps reserve. The battalion commander

and I visited the III Corps command post frequently to attend daily

briefings, meet with III Corps Vietnamese staff members and their

American counterparts, and generally keep abreast of the tactical

situation throughout III Corps.

On 28 December an unidentified enemy force of undetermined strength attacked and seized the village of Binh Gia, which was occupied by 6,000 to 8,000 Catholic refugees who had fled North Vietnam years earlier. Although they initially put up a valiant fight, the village militiamen were vastly outnumbered. They broke contact and either fled or went into hiding. Subsequently, two Ranger companies of the 30th Ranger Battalion counterattacked from the west, but they too were driven off.. It seemed clear that a sizable enemy force occupied Binh Gia and was determined to hold the village. On 29 December III Corps committed the rest of the 30th Ranger Battalion and the 33d Ranger Battalion to the battle. During this phase of the battle, two U.S. Army airmobile helicopters were shot down, half of the 33d Ranger Battalion was surrounded and overrun, and two U.S. Army advisors to the 33d were captured. The determined Rangers continued to press their attack and, with air support, were able to secure a foothold in the village. The Rangers continued to battle the enemy throughout the night and successfully repulsed enemy attempts to dislodge them. Information now available to III Corps should have left little doubt that a very sizable enemy force was in control of Binh Gia.

Later on the 29th our battalion was issued a warning order to make preparations to be committed to the battle during the morning of 30 December, to attack and dislodge the enemy from Binh Gia. The battalion commander (Maj Nho) and I, my assistant (1stLt Phillip Brady, who had joined the battalion 1 month earlier), and battalion staff officers coordinated with our counterparts at III Corps to obtain maps of the area and current operational and intelligence information. Coordination was made with the U.S. Army helicopter organization tasked to lift us into the selected landing zone (LZ) northwest of the village, arrangements were made for suppressive fires by A1–E fixed-wing aircraft and armed helicopters, and radio frequencies were exchanged. It was determined during this period of coordination that there would be no artillery support as we would be out of range of all operational artillery units, and III Corps chose not to move any in place to support us in what portended to be heavy fighting.

At approximately 0830 on 30 December the first wave of helicopters carrying the battalion lifted off from Bien Hoa Airbase. Although air support delivered suppressive fire around the LZ, there were no reports of enemy fire, and the battalion arrived unopposed, as was our movement into Binh Gia from the west. The battalion moved cautiously through the village, to the far end, conducting a thorough search of the area as they did so. Villagers reported that the enemy had hastily withdrawn to the east, leaving behind 32 dead from the previous day’s battle. Villagers also reported that the enemy force numbered at least 750. Reports were made of North Vietnamese and Chinese being among them. If correct, and the intensity of the fighting to that point indicated that it was, it meant that at least a multibattalion-sized enemy force had attacked and occupied the village. Additionally, the defensive positions dug by the enemy while they occupied the village were an indication that they were well led and disciplined. After securing the village the battalion assisted in the evacuation of the dead and wounded Rangers from the earlier battles and, along with the Ranger survivors, established a defense of the village. At this point the 4th Battalion had accomplished its assigned mission and awaited further orders from III Corps.

Late in the day an armed helicopter commenced an attack on a location about 1,500 meters southeast of the village where a large concentration of enemy troops had been observed earlier. During this attack, which I observed, the helicopter was shot down by enemy antiaircraft fire from the same general area that the helicopter was attacking. The helicopter caught fire and descended at a very steep angle, weapons still firing, until it crashed and burst into flames. This crash set in motion a series of events that would have tragic consequences for the 4th Battalion. Although there was little chance that anyone could have survived the crash, III Corps ordered that a patrol be sent out “immediately” to check to determine the situation at the crash site, whether anyone could have survived and, if not, to recover the remains of the crewmen. Maj Nho spoke to the commander of the operation, and I spoke to his American advisor, informing them that it was highly unlikely that there were any survivors of the crash. The outcome of these discussions was a decision to send out a patrol the following morning as it was already late in the day. That evening the enemy conducted probing attacks against the village but were unable to penetrate our defense. Flares were dropped throughout the night, and fixed-wing aircraft supported our defensive fires.

Early the next day, 31 December, the company-sized patrol departed from the southeast corner of the village on a compass azimuth heading toward the crash site. I accompanied the patrol to coordinate air support if needed. We had armed helicopters on station and A1–E fixed-wing bombers on strip alert at Binh Hoa Airbase. Other than the aircraft, we had only our organic crew-served weapons to support the patrol. The absence of artillery support weighed heavily on me as we moved carefully through the wooded area toward the crash site and into what most certainly was an enemy occupied area. Upon reaching the crash site, just inside a rubber plantation, it was determined that there could not possibly have been any survivors. The helicopter had burned completely, and all that remained was a charred mass about 8 feet in diameter. Off to the side there were several mounds of earth, an indication that the enemy had buried the crewmembers’ remains. The company commander established a tight perimeter around the crash site, and Marines began to recover the remains of the helicopter crew. At about this time, as Marines were moving into position along the perimeter, three to five enemy troops were sighted. They were immediately taken under fire and one dropped dead, having been hit in the head. The others managed to escape. I moved over to the enemy who was shot with two other Marines to examine the body. My examination revealed a well-nourished soldier, about 180 pounds, approximately 6 feet tall, clothed in a complete, clean uniform with cartridge belt and armed with a carbine. No means of identification were found on his body. All things considered, I concluded that he could very well have been a North Vietnamese or Chinese soldier.

After this encounter, other enemy troops were observed closing on our perimeter. Soon the entire company was engaged with the enemy, and we began to receive heavy fire from mortars, automatic weapons, and antitank weapons. I reported this information to the on-station aircraft and called in airstrikes just beyond our perimeter. The aircraft on station had a good fix on our location as the helicopter crash site was easily seen from above. I also called for the A1–E fixed-wing bombers that were on alert at Bien Hoa. At this point, further efforts to recover the downed crewmen ceased because everyone was fully engaged in the fight. Casualties began to mount as the enemy advanced on us, now in human wave assaults, encouraged on by the sound of bugles. The only cover available to us was that provided by the rubber trees, but the Marines and supporting aircraft were able to inflict what most certainly were heavy casualties on the attacking enemy as they advanced toward us.

At about this time a bullet struck my helmet and knocked me down. As I began to recover from the blow, I initially could not see anything, and my eyes were burning badly. I instinctively rubbed my eyes and as my vision began to get better, my first sight was of two long jets of blood projecting out from my face. I began to reach for the compress bandage that was on my cartridge belt, but before I could get to it a Vietnamese corpsman was at my side, smiling from ear to ear, and took quick action to bandage my wounds. I had come to learn that most Vietnamese Marines smile when things are really bad, so I took that as a bad sign. Later examination of my helmet revealed that the bullet had struck my helmet on the rim and had shattered. Portions had deflected down and partially severed my nose and caused other facial injuries. Had the bullet impacted a fraction of an inch higher or lower it would most likely have been a fatal wound. I then began to look for my radio operator, but he was nowhere to be seen, so I moved to the company commander’s position to use his radio, but he had also lost communications when his radio had been hit.

We were now receiving heavy fire from several different directions as the enemy continued their assault, darting from rubber tree to rubber tree. Marines began to withdraw from the forward perimeter, and we held them up in the vicinity of the downed helicopter. With the enemy closing in on us, and considering the possibility that we could be surrounded completely, the company commander gave the order to withdraw. The company broke contact and, under covering fire, withdrew to the north and then toward Binh Gia, taking all of its wounded but having to leave behind 12 dead Marines in addition to the remains of the helicopter crewmen. On the way back to Binh Gia, a U.S. Army medical evacuation helicopter landed, and we evacuated several wounded Marines. Arriving back at Binh Gia, the company commander and I provided a thorough rundown to the battalion commander on the enemy force we had encountered at the crash site, making it clear that it was a very sizable force of well-armed, disciplined soldiers, with heavy fire support from mortars, automatic weapons, and antitank weapons. Following this debriefing, at the suggestion of the battalion commander to obtain medical care, I moved to a location inside the village where he told me a helicopter had landed. I was later evacuated to the Saigon Naval Hospital where I underwent surgery for my wounds.

It is unclear who made the decision for the battalion to move back out to the crash site. Whether Maj Nho was ordered to go or whether he reached that decision on his own was not known. Both he and his executive officer had many years of combat experience, and although aggressive in battle, they were not prone to take unnecessary risks. The decision to send out the company-sized patrol into an enemy controlled area had been a calculated risk that had been reluctantly taken by Maj Nho. Now, with the latest information obtained at the crash site, combined with the outcomes from the previous days’ battles, the lack of artillery support, and the fact that the enemy was fighting on terrain favorable to them, serious questions existed as to the wisdom of going back out immediately without reinforcements. Nevertheless, Maj Nho later moved the battalion, minus one company that he left to defend Binh Gia, back to the crash site. The remains of the helicopter crewmen were evacuated, but before the 12 Vietnamese Marines killed in action (KIA) could be evacuated, the battalion was taken under heavy attack by what was later determined to be elements of two VC regiments from the recently formed 9th VC Division, the largest enemy force to have been committed to battle up to that point in time. They were supported by the 80th Artillery Group, led by North Vietnamese officers, which was equipped with 81mm mortars, 70mm howitzers, 75mm recoilless rifles, and 12.7mm heavy antiaircraft machineguns. This force possessed significant firepower, was led by a general, and vastly outnumbered the 4th Battalion by at least 7 or 8 to 1.

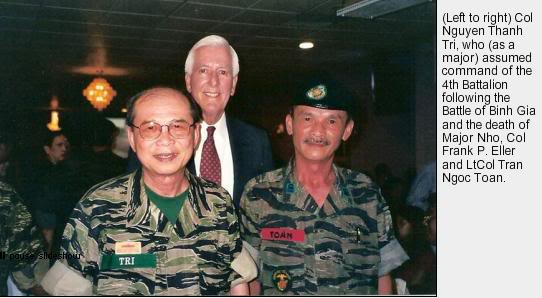

Outnumbered and with woefully inadequate fire support, the Marines fought valiantly but could not prevail against such overwhelming odds. One of the companies, taking heavy casualties, fought its way back to Binh Gia. One was overrun, and the third managed to fight on to nightfall at which time a few survivors were able to exfiltrate the battle area and make their way back to Binh Gia. When the last shot had been fired, the 4th Battalion had suffered 122 KIA, including 29 of the battalion’s 35 officers, and 71 wounded. In addition, Marine Capt Donald Cook, who had been assigned to the battalion for 30 days temporary duty as an observer, was wounded and captured. (For a detailed account of Capt Cook’s capture and the period of time he spent in captivity prior to his death in 1967, refer to the book The First Marine Captured in Vietnam: A Biography of Donald G. Cook, by Donald L. Price, McFarland & Company, Inc., reviewed in MCG, Jul07)..

1stLt Tran Ngoc Toan, Commanding Officer, 1st Company, provided a firsthand account of the battle.. He noted that a number of Marines were killed or wounded during the heavy artillery or mortar barrages that preceded the human wave assaults that followed. Suffering heavy casualties, the few surviving members of the 3d Company reinforced the defensive perimeter that 1stLt Toan had established, and together they repulsed several assaults on their position. With nightfall descending over the battlefield and twice wounded, 1stLt Toan assessed the situation. With only a little over a dozen or so of his men left, he ordered them to exfiltrate the area and try to make it back to Binh Gia. Unable to leave because of his wounds, he ordered his radio operator to leave him. He then lay down by the body of a dead Marine and played dead. Later a VC soldier came along and fired a burst of his weapon at 1stLt Toan. Although one round penetrated his chest, luckily it did not hit any vital organs. During the evening the VC moved about the battlefield executing wounded Marines; stripping their bodies of their weapons, boots, and uniforms; and evacuating their own dead and wounded. 1stLt Toan was finally recovered from the battlefield on the morning of 3 January 1965, 3 days after his encounter in the rubber plantation. Vietnamese and American casualties (killed and wounded) during the 4 days of battles exceeded 400. Estimates of enemy casualties ranged as high as 600, although only 32 enemy bodies were confirmed.

Following my discharge from the hospital 10 days later, I reported back for duty with the 4th Battalion. By this time three additional Marine Corps battalions, three airborne battalions, and one additional Ranger battalion had been committed to a massive search operation of the area surrounding Binh Gia in the hope of engaging the enemy, but they had departed the area. What they did discover was a large tunnel complex that included huge caverns with wooden supports, each of which could protect a large number of troops from air or artillery bombardment. In addition to the tunnel complex, they discovered a number of camouflaged, thatch-roofed buildings, some of which contained rows of beds, and an extensive trench complex that led from the dormitories to antiaircraft emplacements.

After my return to Vung Tau, I visited wounded Marines in their hospital wards. The sight of all of the Marines in the hospital beds, many in arm, leg, or full body casts or with intravenous tubes in their bodies, will remain with me always as will my visit to the cemetery where all but 18 of the 112 Marines who were killed were buried. During this time I also wrote condolence letters, and during the Tet season, along with the battalion executive officer, visited Mrs. Nho to extend my personal condolences.

The fact that the VC had secretly formed a division, moved it across the country to the coast, and outfitted it with 400 tons of weapons and other equipment/supplies from a trawler that had eluded coastal patrols had caught the South Vietnamese Government and Military Advisory Command Vietnam by complete surprise. It was feared that Binh Gia represented the VC’s move to stage three of the insurgency—conventional warfare—rather than tota reliance on hit-and-run tactics.

In the months immediately following Binh Gia, government forces suffered other major losses amounting to an average of one battalion being rendered combat ineffective each week and one district town lost to VC control each month. There was also another coup, further destabilizing the fragile political situation. In February the VC launched an attack on Camp Holloway, resulting in 7 Americans KIA, over 100 wounded in action, and 25 aircraft damaged or destroyed. Following this attack, President Lyndon B. Johnson made the decision to send in U.S. ground forces. U.S. Marines landed at Da Nang to defend the Da Nang Airbase on 8 March 1965. This marked the end of the beginning of the war that theretofore had consisted only of military/civilian advisors and materiel and other logistics support. Henceforth the number of combat forces introduced into the war, by both sides of the conflict, would increase, and the war would expand in scope. Unknown at the time was the fact that the North Vietnamese had reached a decision in late 1964, encouraged by VC gains made in the preceding year, to send North Vietnamese combat forces to South Vietnam. They had already begun to arrive in early 1965.

MỤC LỤC

Điếu văn vĩnh biệt cựu Đại Tá Nguyễn Năng Bảo

Những ngày hành quân Cồn Thiên

Người lính VNCH sau 30 Tháng Tư

Người Tây phương tính năm lịch theo mặt trời

Một hội nghị với nhiều ư nghĩa

Tấm thẻ bài cho người nằm xuống

TĐ4 TQLC và Những ngày tháng sau cùng

Thôi ! Ḿnh về Linh Xuân Thôn đi em

Tiến tŕnh thành lập Chiến Đoàn và Lữ Đoàn